|

History

Native American inhabitation

Some of the oldest stone tools found in Minnesota. The oldest known human remains in Minnesota, dating back about 9000 years ago, were discovered near Browns Valley in 1933. "Browns Valley Man" was found with tools of the Clovis and Folsom types. Some of the earliest evidence of a sustained presence in the area comes from a site known as Bradbury Brook near Mille Lacs Lake which was used around 7500 BC. Subsequently, extensive trading networks developed in the region. The body of an early resident known as "Minnesota Woman" was discovered in 1931 in Otter Tail County. Radiocarbon dating places the age of the bones approximately 8,000 years ago, near the end of the Eastern Archaic period. She had a conch shell from a snail species known as Busycon perversa, which had previously only been known to exist in Florida.

|

Ojibwa women in canoe, Leech Lake, 1909

|

Several hundred years later, the climate of Minnesota warmed significantly. As large animals such as mammoths became extinct, native people changed their diet. They gathered nuts, berries, and vegetables, and they hunted smaller animals such as deer, bison, and birds. The stone tools found from this era became smaller and more specialized to use these new food sources. They also devised new techniques for catching fish, such as fish hooks, nets, and harpoons. Around 5000 BC, people on the shores of Lake Superior (in Minnesota and portions of what is now Michigan, Wisconsin, and Canada) were the first on the continent to begin making metal tools. Pieces of ore with high concentrations of copper were initially pounded into a rough shape, heated to reduce brittleness, pounded again to refine the shape, and reheated. Edges could be made sharp enough to be useful as knives or spear points. Archaeological evidence of Native American settlements dates back as far as 3000 BC; the Jeffers Petroglyphs site in southwest Minnesota contains carvings thought to date to the Late Archaic Period (3000 BC to 1000 BC). Around 700 BC, burial mounds were first created, and the practice continued until the arrival of Europeans, when 10,000 such mounds dotted the state. By AD 800, wild rice became a staple crop in the region, and corn farther to the south. Within a few hundred years, the Mississippian culture reached into the southeast portion of the state, and large villages were formed. The Dakota Native American culture may have descended from some of the peoples of the Mississippian culture. When Europeans first started exploring Minnesota, the region was inhabited primarily by tribes of Dakota, with the Ojibwa (sometimes called Chippewa, or Anishinaabe) beginning to migrate westward into the state around 1700. (Other sources suggest the Ojibwe reached Minnesota by 1620 or earlier.) There were also the Chiwere Ioway in the southwest, the Algonquian A'ani to the west, and possibly the Menominee in some parts of the southeast as well as other tribes which could have been either Algonquian or Chiwere to the northeast, alongside Lake Superior (possibilities include the Fauk, Sauk, and Missouria). The economy of these tribes was chiefly based on hunter-gatherer activities. There was also a small group of Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) Native Americans near Long Prairie, who later moved to a reservation in Blue Earth County in 1855. At some early point, the Missouria moved south into what is now Missouri, the Menominee ceded much of their westernmost lands and withdrew closer to the region of Green Bay, Wisconsin, and the A'ani were pushed north and west by the Dakota and split into the Gros Ventre and the Arapaho. Later tribes who would inhabit the region include the Assiniboine, who split from the Dakota and returned to Minnesota, but later also moved west as American settlers came to populate the region.

|

Ruins of old Fond du Lac trading post on the Saint Louis River in 1907

|

European exploration

In the late 1650s, Pierre Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers were likely the first Europeans to meet Dakota Native Americans while following the southern shore of Lake Superior (which would become northern Wisconsin). The north shore was explored in the 1660s. Among the first to do this was Claude Allouez, a missionary on Madeline Island. He made an early map of the area in 1671. Around this time, the Ojibwa Native Americans reached Minnesota as part of a westward migration. Having come from a region around Maine, they were experienced at dealing with European traders. They dealt in furs and possessed guns. Tensions rose between the Ojibwa and Dakota in the ensuing years. In 1671, France signed a treaty with a number of tribes to allow trade. Shortly thereafter, French trader Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut arrived in the area and began trading with the local tribes. Du Lhut explored the western area of Lake Superior, near his namesake, the city of Duluth, and areas south of there. He helped to arrange a peace agreement between the Dakota and Ojibwa tribes in 1679.

|

A painting of Father Hennepin 'discovering' Saint Anthony Falls.

|

Father Louis Hennepin with companions Michel Aco and Antoine Auguelle (aka Picard Du Gay) headed north from the area of Illinois after coming into that area with an exploration party headed by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. They were captured by a Dakota tribe in 1680. While with the tribe, they came across and named the Falls of Saint Anthony. Soon, Du Lhut negotiated to have Hennepin's party released from captivity. Hennepin returned to Europe and wrote a book, Description of Louisiana, published in 1683, about his travels where many portions (including the part about Saint Anthony Falls) were strongly embellished. As an example, he described the falls as being a drop of fifty or sixty feet, when they were really only about sixteen feet. Pierre-Charles Le Sueur explored the Minnesota River to the Blue Earth area around 1700. He thought the blue earth was a source of copper, and he told stories about the possibility of mineral wealth, but there actually was no copper to be found. Explorers searching for the fabled Northwest Passage and large inland seas in North America continued to pass through the state. In 1721, the French built Fort Beauharnois on Lake Pepin. In 1731, the Grand Portage trail was first traversed by a European, Pierre La Vérendrye. He used a map written down on a piece of birch bark by Ochagach, an Assiniboine guide. The North West Company, which traded in fur and competed with the Hudson's Bay Company, was established along the Grand Portage in 1783-1784. Jonathan Carver, a shoemaker from Massachusetts, visited the area in 1767 as part of another expedition. He and the rest of the exploration party were only able to stay for a relatively short period, due to supply shortages. They headed back east to Fort Michilimackinac, where Carver wrote journals about the trip, though others would later claim the stories were largely plagiarized from others. The stories were published in 1778, but Carver died before the book earned him much money. Carver County and Carver's Cave are named for him.

Until 1818 the Red River Valley was considered British and was subject to several colonization schemes, such as the Red River Colony. The boundary where the Red River crossed the 49th parallel was not marked until 1823, when Stephen H. Long conducted a survey expedition. When several hundred settlers abandoned the Red River Colony in the 1820s, they entered the United States by way of the Red River Valley, instead of moving to eastern Canada or returning to Europe. The region had been occupied by Métis people, the children of voyageurs and Native Americans, since the middle 17th century. Several efforts were made to determine the source of the Mississippi River. The true source was found in 1832, when Henry Schoolcraft was guided by a group of Ojibwa headed by Ozaawindib ("Yellow Head") to a lake in northern Minnesota. Schoolcraft named it Lake Itasca, combining the Latin words veritas ("truth") and caput ("head"). The native name for the lake was Omashkooz, meaning elk. Other explorers of the area include Zebulon Pike in 1806, Major Stephen Long in 1817, George William Featherstonhaugh in 1835, and John Pope (military officer) in 1849. Featherstonhaugh conducted a geological survey of the Minnesota River valley and wrote an account entitled A Canoe Voyage up the Minnay Sotor. Joseph Nicollet scouted the area in the late 1830s, exploring and mapping the Upper Mississippi River basin, the St. Croix River, and the land between the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. He and John C. Frémont left their mark in the southwest of the state, carving their names in the pipestone quarries near Winnewissa Falls (an area now part of Pipestone National Monument in Pipestone County). Henry Wadsworth Longfellow never explored the state, but he did help to make it popular. He published The Song of Hiawatha in 1855, which contains references to many regions in Minnesota. The story was based on Ojibwa legends carried back east by other explorers and traders (particularly those collected by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft).

All

of the land east of the Mississippi River was

granted to the United States by the Second Treaty

of Paris at the end of the American Revolution in

1783. This included what would become modern day

Saint Paul but only part of Minneapolis, including

the northeast, north-central and east-central

portions of the state. The western portion of the

state was part of the Spanish Louisiana since the

Treaty of Fontainebleau, in 1762. The wording of

the treaty in the Minnesota area depended on

landmarks reported by fur traders, who erroneously

reported an "Isle Phelipeaux" in Lake Superior, a

"Long Lake" west of the island, and the belief

that the Mississippi River ran well into modern

Canada. Most of the state was purchased in 1803

from France as part of the Louisiana Purchase.

Parts of northern Minnesota were considered to be

in Rupert's Land. The exact definition of the

boundary between Minnesota and British North

America was not addressed until the Anglo-American

Convention of 1818, which set the U.S.-Canada

border at the 49th parallel west of the Lake of

the Woods (except for a small chunk of land now

dubbed the Northwest Angle). Border disputes east

of the Lake of the Woods continued until the

Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842. Throughout the

first half of the 19th century, the northeastern

portion of the state was a part of the Northwest

Territory, then the Illinois Territory, then the

Michigan Territory, and finally the Wisconsin

Territory. The western and southern areas of the

state, although theoretically part of the

Wisconsin Territory from its creation in 1836,

were not formally organized until 1838, when they

became part of the Iowa Territory.

|

Fort

Snelling |

Fort

Snelling was the first major U.S. military

presence in the state. The land for the fort, at

the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi

rivers, was acquired in 1805 by Zebulon Pike. When

concerns mounted about the fur trade in the area,

construction of the fort began in 1819.

Construction was completed in 1825, and Colonel

Josiah Snelling and his officers and soldiers left

their imprint on the area. One of the missions of

the fort was to mediate disputes between the

Ojibwe and the Dakota tribes. Lawrence Taliaferro

was an agent of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs.

He spent 20 years at the site, finally resigning

in 1839.

In the 1850s, Fort Snelling

played a key role in the infamous Dred Scott court

case. Slaves Dred Scott and his wife were taken to

the fort by their master, John Emerson. They lived

at the fort and elsewhere in territories where

slavery was prohibited. After Emerson's death, the

Scotts argued that since they had lived in free

territory, they were no longer slaves. Ultimately,

the U.S. Supreme Court sided against the Scotts.

Dred Scott Field, located just a short distance

away in Bloomington, is named in the memory of

Fort Snelling's significance in one of the most

important legal precedents in U.S. History. By

1851, treaties between Native American tribes and

the U.S. government had opened much of Minnesota

to settlement, so Fort Snelling no longer was a

frontier outpost. It served as a training center

for soldiers during the American Civil War and

later as the headquarters for the Department of

Dakota. A portion has been designated as Fort

Snelling National Cemetery where over 160,000 are

interred. During World War II, the fort served as

a training center for nearly 300,000 inductees.

After World War II, the fort was threatened with

demolition due to the building of freeways Highway

5 and Highway 55, but citizens rallied to save it.

Fort Snelling is now a historic site operated by

the Minnesota Historical Society. Fort Snelling

was largely responsible for the establishment of

the city of Minneapolis. In an effort to be

self-sufficient, the soldiers of the fort built

roads, planted crops, and built a grist mill and a

sawmill at Saint Anthony Falls. Later, Franklin

Steele came to Fort Snelling as the post sutler

(the operator of the general store), and

established interests in lumbering and other

activities. When the Ojibwe signed a treaty ceding

lands in 1837, Steele staked a claim to land on

the east side of the Mississippi River adjacent to

Saint Anthony Falls. In 1848, he built a sawmill

at the falls, and the community of Saint Anthony

sprung up around the east side of the falls.

Steele told one of his employees, John H. Stevens,

that land on the west side of the falls would make

a good site for future mills. Since the land on

the west side was still part of the military

reservation, Stevens made a deal with Fort

Snelling's commander. Stevens would provide free

ferry service across the river in exchange for a

tract of 160 acres (0.65 km2) at the head of the

falls. Stevens received the claim and built a

house, the first house in Minneapolis, in 1850. In

1854, Stevens platted the city of Minneapolis on

the west bank. Later, in 1872, Minneapolis

absorbed the city of Saint Anthony. The city of

Saint Paul, Minnesota owes its existence to Fort

Snelling. A group of squatters, mostly from the

ill-fated Red River Colony in what is now the

Canadian province of Manitoba, established a camp

near the fort. The commandant of Fort Snelling,

Major Joseph Plympton, found their presence

problematic because they were using timber and

allowing their cattle and horses to graze around

the fort. Plympton banned lumbering and the

construction of any new buildings on the military

reservation land. As a result, the squatters moved

four miles downstream on the Mississippi River.

They settled at a site known as Fountain Cave.

This site was not quite far enough for the

officers at the fort, so the squatters were forced

out again. Pierre "Pig's Eye" Parrant, a popular

moonshiner among the group, moved downriver and

established a saloon, becoming the first European

resident in the area that later became Saint Paul.

The squatters named their settlement "Pig's Eye"

after Parrant. The name was later changed to

Lambert's Landing and then finally Saint Paul.

However, the earliest name for the area comes from

a Native American colony Im-in-i-ja Ska, meaning

"White Rock" and referring to the limestone bluffs

nearby. In the 1850s, Fort Snelling

played a key role in the infamous Dred Scott court

case. Slaves Dred Scott and his wife were taken to

the fort by their master, John Emerson. They lived

at the fort and elsewhere in territories where

slavery was prohibited. After Emerson's death, the

Scotts argued that since they had lived in free

territory, they were no longer slaves. Ultimately,

the U.S. Supreme Court sided against the Scotts.

Dred Scott Field, located just a short distance

away in Bloomington, is named in the memory of

Fort Snelling's significance in one of the most

important legal precedents in U.S. History. By

1851, treaties between Native American tribes and

the U.S. government had opened much of Minnesota

to settlement, so Fort Snelling no longer was a

frontier outpost. It served as a training center

for soldiers during the American Civil War and

later as the headquarters for the Department of

Dakota. A portion has been designated as Fort

Snelling National Cemetery where over 160,000 are

interred. During World War II, the fort served as

a training center for nearly 300,000 inductees.

After World War II, the fort was threatened with

demolition due to the building of freeways Highway

5 and Highway 55, but citizens rallied to save it.

Fort Snelling is now a historic site operated by

the Minnesota Historical Society. Fort Snelling

was largely responsible for the establishment of

the city of Minneapolis. In an effort to be

self-sufficient, the soldiers of the fort built

roads, planted crops, and built a grist mill and a

sawmill at Saint Anthony Falls. Later, Franklin

Steele came to Fort Snelling as the post sutler

(the operator of the general store), and

established interests in lumbering and other

activities. When the Ojibwe signed a treaty ceding

lands in 1837, Steele staked a claim to land on

the east side of the Mississippi River adjacent to

Saint Anthony Falls. In 1848, he built a sawmill

at the falls, and the community of Saint Anthony

sprung up around the east side of the falls.

Steele told one of his employees, John H. Stevens,

that land on the west side of the falls would make

a good site for future mills. Since the land on

the west side was still part of the military

reservation, Stevens made a deal with Fort

Snelling's commander. Stevens would provide free

ferry service across the river in exchange for a

tract of 160 acres (0.65 km2) at the head of the

falls. Stevens received the claim and built a

house, the first house in Minneapolis, in 1850. In

1854, Stevens platted the city of Minneapolis on

the west bank. Later, in 1872, Minneapolis

absorbed the city of Saint Anthony. The city of

Saint Paul, Minnesota owes its existence to Fort

Snelling. A group of squatters, mostly from the

ill-fated Red River Colony in what is now the

Canadian province of Manitoba, established a camp

near the fort. The commandant of Fort Snelling,

Major Joseph Plympton, found their presence

problematic because they were using timber and

allowing their cattle and horses to graze around

the fort. Plympton banned lumbering and the

construction of any new buildings on the military

reservation land. As a result, the squatters moved

four miles downstream on the Mississippi River.

They settled at a site known as Fountain Cave.

This site was not quite far enough for the

officers at the fort, so the squatters were forced

out again. Pierre "Pig's Eye" Parrant, a popular

moonshiner among the group, moved downriver and

established a saloon, becoming the first European

resident in the area that later became Saint Paul.

The squatters named their settlement "Pig's Eye"

after Parrant. The name was later changed to

Lambert's Landing and then finally Saint Paul.

However, the earliest name for the area comes from

a Native American colony Im-in-i-ja Ska, meaning

"White Rock" and referring to the limestone bluffs

nearby.

Minneapolis and Saint Paul

are collectively known as the "Twin Cities". The

cities enjoyed a rivalry during their early years,

with Saint Paul being the capital city and

Minneapolis becoming prominent through industry.

The term "Twin Cities" was coined around 1872,

after a newspaper editorial suggested that

Minneapolis could absorb Saint Paul. Residents

decided that the cities needed a separate

identity, so people coined the phrase "Dual

Cities", which later evolved into "Twin Cities".

Today, Minneapolis is the largest city in

Minnesota, with a population of 382,618 in the

2000 census. Saint Paul is the second largest

city, with a population of 287,151. Minneapolis

and Saint Paul anchor a metropolitan area with a

population of 2,968,806 as of 2000, with a total

state population of 4,919,479.

Home of

Henry Hastings Sibley Home of

Henry Hastings Sibley

Henry Hastings Sibley built

the first stone house in the Minnesota Territory

in Mendota in 1838, along with other limestone

buildings used by the American Fur Company, which

bought animal pelts at that location from 1825 to

1853.[51] Another area of early economic

development in Minnesota was the logging industry.

Loggers found the white pine especially valuable,

and it was plentiful in the northeastern section

of the state and in the St. Croix River valley.

Before railroads, lumbermen relied mostly on river

transportation to bring logs to market, which made

Minnesota's timber resources attractive. Towns

like Marine on St. Croix and Stillwater became

important lumber centers fed by the St. Croix

River, while Winona was supplied lumber by areas

in southern Minnesota and along the Minnesota

River. The unregulated logging practices of the

time and a severe drought took their toll in 1894,

when the Great Hinckley Fire ravaged 480 square

miles in the Hinckley and Sandstone areas of Pine

County, killing over 400 residents. The

combination of logging and drought struck again in

the Baudette Fire of 1910 and the Cloquet Fire of

1918.

Logging pine 1860's-1870's Logging pine 1860's-1870's

Saint Anthony, on the east

bank of the Mississippi River later became part of

Minneapolis, and was an important lumber milling

center supplied by the Rum River. In 1848,

businessman Franklin Steele built the first

private sawmill on the Saint Anthony Falls, and

more sawmills quickly followed. The oldest home

still standing in Saint Anthony is the Ard Godfrey

house, built in 1848, and lived in by Ard and

Harriet Godfrey. The house of John H. Stevens, the

first house on the west bank in Minneapolis, was

moved several times, finally to Minnehaha Park in

south Minneapolis in 1896.

Minnesota

Territory

Stephen A. Douglas (D), the

chair of the Senate Committee on Territories,

drafted the bill authorizing Minnesota Territory.

He had envisioned a future for the upper

Mississippi valley, so he was motivated to keep

the area from being carved up by neighboring

territories. In 1846, he prevented Iowa from

including Fort Snelling and Saint Anthony Falls

within its northern border. In 1847, he kept the

organizers of Wisconsin from including Saint Paul

and Saint Anthony Falls. The Minnesota Territory

was established from the lands remaining from Iowa

Territory and Wisconsin Territory on March 3,

1849. The Minnesota Territory extended far into

what is now North Dakota and South Dakota, to the

Missouri River. There was a dispute over the shape

of the state to be carved out of Minnesota

Territory. An alternate proposal that was only

narrowly defeated would have made the 46th

parallel the state's northern border and the

Missouri River its western border, thus giving up

the whole northern half of the state in exchange

for the eastern half of what later became South

Dakota. With Alexander Ramsey (W) as the first

governor of Minnesota Territory and Henry Hastings

Sibley (D) as the territorial delegate to the

United States Congress, the populations of Saint

Paul and Saint Anthony swelled. Henry M. Rice (D),

who replaced Sibley as the territorial delegate in

1853, worked in Congress to promote Minnesota

interests. He lobbied for the construction of a

railroad connecting Saint Paul and Lake Superior,

with a link from Saint Paul to the Illinois

Central.

Statehood

In December 1856, Rice

brought forward two bills in Congress: an enabling

act that would allow Minnesota to form a state

constitution, and a railroad land grant bill.

Rice's enabling act defined a state containing

both prairie and forest lands. The state was

bounded on the south by Iowa, on the east by

Wisconsin, on the north by Canada, and on the west

by the Red River of the North and the Bois de

Sioux River, Lake Traverse, Big Stone Lake, and

then a line extending due south to the Iowa

border. Rice made this motion based on Minnesota's

population growth. At the time, tensions between

the northern and the southern United States were

growing, in a series of conflicts that eventually

resulted in the American Civil War. There was

little debate in the United States House of

Representatives, but when Stephen A. Douglas

introduced the bill in the United States Senate,

it caused a firestorm of debate. Northerners saw

their chance to add two senators to the side of

the free states, while Southerners were sure that

they would lose power. Many senators offered

polite arguments that the population was too

sparse and that statehood was premature. Senator

John Burton Thompson of Kentucky, in particular,

argued that new states would cost the government

too much for roads, canals, forts, and

lighthouses. Although Thompson and 21 other

senators voted against statehood, the enabling act

was passed on February 26, 1857. After the

enabling act was passed, territorial legislators

had a difficult time writing a state constitution.

A constitutional convention was assembled in July

1857, but Republicans and Democrats were deeply

divided. In fact, they formed two separate

constitutional conventions and drafted two

separate constitutions. Eventually, the two groups

formed a conference committee and worked out a

common constitution. The divisions continued,

though, because Republicans refused to sign a

document that had Democratic signatures on it, and

vice versa. One copy of the constitution was

written on white paper and signed only by

Republicans, while the other copy was written on

blue-tinged paper and signed by Democrats. These

copies were signed on August 29, 1857. An election

was called on October 13, 1857, where Minnesota

residents would vote to approve or disapprove the

constitution. The constitution was approved by

30,055 voters, while 571 rejected it. The state

constitution was sent to the United States

Congress for ratification in December 1857. The

approval process was drawn out for several months

while Congress debated over issues that had

stemmed from the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Southerners

had been arguing that the next state should be

pro-slavery, so when Kansas submitted the

pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, the Minnesota

statehood bill was delayed. After that,

Northerners feared that Minnesota's Democratic

delegation would support slavery in Kansas.

Finally, after the Kansas question was settled and

after Congress decided how many representatives

Minnesota would get in the House of

Representatives, the bill passed. The eastern half

of the Minnesota Territory, under the boundaries

defined by Henry Mower Rice, became the country's

32nd state on May 11, 1858. The western part

remained unorganized until its incorporation into

the Dakota Territory on March 2,

1861.

Civil

War era and Dakota War of 1862

Minnesota strongly supported

the Union war effort, with about 22,000

Minnesotans serving. The 1st Minnesota Volunteer

Infantry was particularly important to the Battle

of Gettysburg. Governor Alexander Ramsey happened

to be in Washington D.C. when Ft. Sumter was fired

upon. He went immediately to the White House and

made his state the first to offer help in putting

down the rebellion. At the same time, the state

faced another crisis as the Dakota War of 1862

broke out. The Dakota had signed the Treaty of

Traverse des Sioux and Treaty of Mendota in 1851

because they were concerned that without money

from the United States government, they would

starve, due to the loss of habitat of huntable

game. They were initially given a strip of land of

ten miles north and south of the Minnesota River,

but they were later forced to sell the northern

half of the land. In 1862, crop failures left the

Dakota with food shortages, and government money

was delayed. After four young Dakota men,

searching for food, shot a family of white

settlers near Acton, the Dakota leadership decided

to continue the attacks in an effort to drive out

the settlers. Over a period of several days,

Dakota attacks at the Lower Sioux Agency, New Ulm

and Hutchinson, as well as in the surrounding

farmlands, resulted in the deaths of at least 300

to 400 white settlers and government employees,

causing panic in the settlements and provoking

counterattacks by state militia and federal forces

which spread throughout the Minnesota River Valley

and as far away as the Red River Valley. The

ensuing battles at Fort Ridgely, Birch Coulee,

Fort Abercrombie, and Wood Lake punctuated a

six-week war, which ended with the trial of 425

Native Americans for their participation in the

war. Of this number, 303 men were convicted and

sentenced to death.

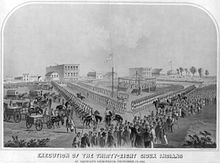

Mass

hanging in Mankato, Minnesota. Mass

hanging in Mankato, Minnesota.

Episcopal Bishop Henry

Benjamin Whipple pleaded to President Abraham

Lincoln for clemency, and the death sentences of

all but 39 men were reduced to prison terms. On

December 26, 1862, 38 men were hanged by the U.S.

Army at Mankato-the largest mass execution in the

United States. Many of the remaining Dakota Native

Americans, including non-combatants, were confined

in a prison camp at Pike Island over the winter of

1862-1863, where more than 300 died of disease.

Survivors were later exiled to the Crow Creek

Reservation, then later to a reservation near

Niobrara, Nebraska.

A

small number of Dakota Native Americans managed to

return to Minnesota in the 1880s and establish

communities near Granite Falls, Morton, Prior

Lake, and Red Wing. However, after this time

Dakota people were no longer allowed to reside in

Minnesota with the exception of the meritorious

Sioux called the Loyal Mdewakanton. This separate

class of Dakota did not participate in the Dakota

War of 1862, since they were assimilated

Christians and instead decided to help some of the

missionaries escape the Sioux warriors who chose

to fight.

Farming and railroad

development

After the

Civil War, Minnesota became an attractive region

for European immigration and settlement as

farmland. Minnesota's population in 1870 was

439,000; this number tripled during the two

subsequent decades. The Homestead Act in 1862

facilitated land claims by settlers, who regarded

the land as being cheap and fertile. The railroad

industry, led by the Northern Pacific Railway and

Saint Paul and Pacific Railroad, advertised the

many opportunities in the state and worked to get

immigrants to settle in Minnesota. James J. Hill,

in particular, was instrumental in reorganizing

the Saint Paul and Pacific Railroad and extending

lines from the Minneapolis-Saint Paul area into

the Red River Valley and to Winnipeg. Hill was

also responsible for building a new passenger

depot in Minneapolis, served by the landmark Stone

Arch Bridge which was completed in 1883. During

the 1880s, Hill continued building tracks through

North Dakota and Montana. In 1890, the railroad,

now known as the Great Northern Railway, started

building tracks through the mountains west to

Seattle. Other railroads, such as the Lake

Superior and Mississippi Railroad and the

Milwaukee Road, also played an important role in

the early days of Minnesota's statehood. Later

railways, such as the Soo Line and Minneapolis and

St. Louis Railway facilitated the sale of

Minneapolis flour and other products, although

they were not as involved in attracting

settlers.

Oliver Hudson Kelley played

an important role in farming as one of the

founders of the National Grange, along with

several other clerks in the United States

Department of Agriculture. The movement grew out

of his interest in cooperative farm associations

following the end of the Civil War, and he

established local Grange chapters in Elk River and

Saint Paul. The organization worked to provide

education on new farming methods, as well as to

influence government and public opinion on matters

important to farmers. One of these areas of

concern was the freight rates charged by the

railroads and by the grain elevators. Since there

was little or no competition between railroads

serving Minnesota farm communities, railroads

could charge as much as the traffic would bear. By

1871, the situation was so heated that both the

Republican and Democratic candidates in state

elections promised to regulate railroad rates. The

state established an office of railroad

commissioner and imposed maximum charges for

shipping. Populist Ignatius L. Donnelly also

served the Grange as an organizer. Saint Anthony

Falls, the only waterfall of its height on the

Mississippi, played an important part in the

development of Minneapolis. The power of the

waterfall first fueled sawmills, but later it was

tapped to serve flour mills. In 1870, only a small

number of flour mills were in the Minneapolis

area, but by 1900 Minnesota mills were grinding

14.1% of the nation's grain. Advances in

transportation, milling technology, and water

power combined to give Minneapolis a dominance in

the milling industry. Spring wheat could be sown

in the spring and harvested in late summer, but it

posed special problems for milling. To get around

these problems, Minneapolis millers made use of

new technology. They invented the middlings

purifier, a device that used jets of air to remove

the husks from the flour early in the milling

process. They also started using roller mills, as

opposed to grindstones. A series of rollers

gradually broke down the kernels and integrated

the gluten with the starch. These improvements led

to the production of "patent" flour, which

commanded almost double the price of "bakers" or

"clear" flour, which it replaced. Pillsbury and

the Washburn-Crosby Company (a forerunner of

General Mills) became the leaders in the

Minneapolis milling industry. This leadership in

milling later declined as milling was no longer

dependent on water power, but the dominance of the

mills contributed greatly to the economy of

Minneapolis and Minnesota, attracting people and

money to the region.

Industrial

development Industrial

development

Duluth, Missabe and Iron

Range Railway ore docks loading ships,

1900-1915.

At the end of

the 19th century, several forms of industrial

development shaped Minnesota. In 1882, a

hydroelectric power plant was built at Saint

Anthony Falls, marking one of the first

developments of hydroelectric power in the United

States.[76] Iron mining began in northern

Minnesota with the opening of the Soudan Mine in

1884. The Vermilion Range was surveyed and mapped

by a party financed by Charlemagne Tower. Another

mining town, Ely began with the foundation of the

Chandler Mine in 1888. Soon after, the Mesabi

Range was established when ore was found just

under the surface of the ground in Mountain Iron.

The Mesabi Range ultimately had much more ore than

the Vermilion Range, and it was easy to extract

because the ore was closer to the surface. As a

result, open-pit mines became well-established on

the Mesabi Range, with 111 mines operating by

1904. To ship the iron ore to refineries,

railroads such as the Duluth, Missabe and Iron

Range Railway were built from the iron ranges to

Two Harbors and Duluth on Lake Superior. Large ore

docks were used at these cities to load the iron

ore onto ships for transport east on the Great

Lakes. The mining industry helped to propel Duluth

from a small town to a large, thriving city. In

1904, iron was discovered in the Cuyuna Range in

Crow Wing County. Between 1904 and 1984, when

mining ceased, more than 106 million tons of ore

were mined. Iron from the Cuyuna Range also

contained significant proportions of manganese,

increasing its value.

Mayo

Clinic Mayo

Clinic

Statue

of Dr. William Worrall Mayo near the Mayo Clinic

in Rochester

Dr. William

Worrall Mayo, the founder of the Mayo Clinic,

emigrated from Salford, United Kingdom to the

United States in 1846 and became a medical doctor

in 1850. In 1863, Mayo moved to Rochester,

followed by his family the next year. In the

summer of 1883, an F5 tornado struck, dubbed the

1883 Rochester tornado, causing a substantial

number of deaths and injuries. Dr. W. W. Mayo

worked with nuns from the Sisters of St. Francis

to treat the survivors. After the disaster, Mother

Alfred Moes and Dr. Mayo recognized the need for a

hospital and joined together to build the 27-bed

Saint Marys Hospital which opened in 1889. The

hospital, with over 1100 beds, is now part of the

Mayo Clinic, which grew out of the practice of

William Worrall Mayo and his sons, William James

Mayo (1861-1939) and Charles Horace Mayo. Dr.

Henry Stanley Plummer joined the Mayo Brothers'

practice in 1901. Plummer developed many of the

systems of group practice which are universal

around the world today in medicine and other

fields, such as a single medical record and an

interconnecting telephone system.

The information on Trails to

the Past © Copyright

may be used in personal family history research,

with source citation. The pages in entirety may

not be duplicated for publication in any fashion

without the permission of the owner. Commercial

use of any material on this site is not

permitted. Please respect the wishes of

those who have contributed their time and efforts

to make this free site possible.~Thank

you! |